Sofa Prototyping

WHY FIDELITY MATTERS

By Kylie Tuosto

Recently I moved into a new house. We’re still unpacking and getting settled, but it’s starting to feel like home. Our next big project is furniture for the living room. Our current furniture has served us well, but it doesn’t work in the new space. If you have a spouse, you know that the process of agreeing and deciding on these things is never easy.

My husband and I both work in UX, so our first instinct was to prototype different configurations for our new living space. (Sometimes our home life feels like it’s part of an episode of Silicon Valley. All we’re missing is Jared with the post-it notes and scrum board.) We know the style and color we want, but we haven’t decided on a configuration. On that front, we still have lots of questions. Do we want a sitting room for conversation or an entertainment area for lounging and watching TV? Should we optimize for maximum seating or open space? Do we want the area to feel cozy and full or light and open? On top of that, we both feel pressure to get it right the first time. Years ago, we ordered furniture that we wound up having to return. It was a huge hassle, and neither of us wants to go through that again. With so many decisions and the pressure to get them right, we took a Sunday morning to prototype floorplans with blue painters tape.

Different questions require different types of prototypes. And that’s why it’s so important not to let the fidelity of your prototype get ahead of your question. We thought we knew that we wanted a large sofa or sectional, so the question we were asking was, “What size do we want for this space?” With that certainty, we jumped right into a high-fidelity, higher-cost method of prototyping (peeling blue painters tape off the floor does take time). But we quickly realized that the question was actually “What configuration makes the most sense for this space?” From our sticky note sketches, we decided that two of the ten options balanced our requirements. And we were able to quickly prototype those two options—not with painters tape, but with elements of the furniture we already had.

So when you’re feeling stuck or disagreeing—check yourself. Are you asking the right questions? Is your prototyping fidelity too high or too low to answer those questions? With the right questions and the right prototype to test them, you’ll uncover all the answers you need.

Here's what we chose in case you're curious. York sofa by Room & Board.

Getting tactical felt great. As is typical with most design solutions, we jumped straight to our favorite one (a standard sofa with a chaise) and started outlining it on the floor. My husband looked up the measurements while I started taping it out on the floor. That option turned out to be way too small and hardly filled up the space. So we tried another option (a sectional), and that led to a whole new set of questions. Should it be up right against the wall? Would it extend too far into the dining area? Will the corner of the room have enough light? This is where we got stuck. We spent an hour arguing and getting frustrated, pulling up tape and then moving it.

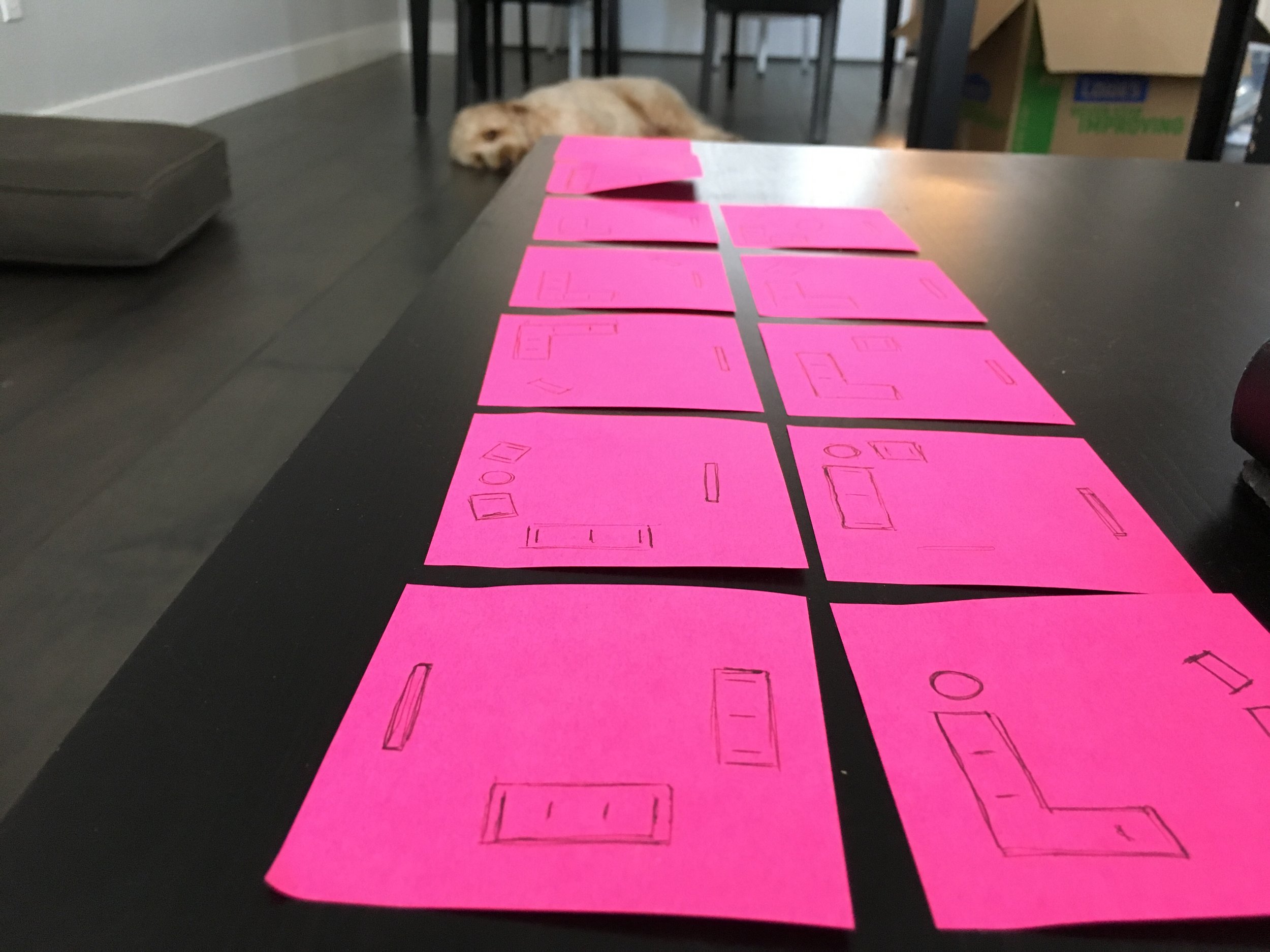

Then I pulled out a pen and some sticky notes. From a bird’s-eye view, I started sketching the options we’d discussed. That turned the conversation from argument to options. What else could we do? How else could we configure it? What if it wasn’t a sectional? What if we had two side chairs or a love seat and a sofa? What started as an argument turned into a brainstorm. Before we knew it, we had 10 options instead of just two.

Trying out two different sizes and a make-shift chaise lounge.

From those 10, we realized there were more important questions we needed to answer than whether we wanted 93” or 105”? The conversation went back to “What’s the focal point of the room?” and “How much seating do we really want?” To our surprise, we agreed on those two points. So we chose two options, took them to the next round of prototyping, and quickly narrowed to one we both felt good about.

Later that afternoon, it struck me that disagreement on minute details can sometimes eclipse agreement on most everything else. As designers, we all know how important it is to make things tangible. And when we find ourselves in difficult conversations, we know the best way to unblock ourselves and our teams is to start making it real. But this example illustrates a more nuanced point than just that. It’s not just that prototyping is good. It’s that the aim of prototyping is to answer unanswered questions. And sometimes our questions are big and sometimes they’re small. Sometimes our questions are “What are customers trying to do?” and sometimes they’re “Will customers understand the options if we present them in a dropdown?”

The aim of prototyping is to answer unanswered questions. And different questions require different types of prototypes.

Ten different configurations and an annoyed puppy in the background.

Different questions require different types of prototypes. And that’s why it’s so important not to let the fidelity of your prototype get ahead of your question. We thought we knew that we wanted a large sofa or sectional, so the question we were asking was, “What size do we want for this space?” With that certainty, we jumped right into a high-fidelity, higher-cost method of prototyping (peeling blue painters tape off the floor does take time). But we quickly realized that the question was actually “What configuration makes the most sense for this space?” From our sticky note sketches, we decided that two of the ten options balanced our requirements. And we were able to quickly prototype those two options—not with painters tape, but with elements of the furniture we already had.

So when you’re feeling stuck or disagreeing—check yourself. Are you asking the right questions? Is your prototyping fidelity too high or too low to answer those questions? With the right questions and the right prototype to test them, you’ll uncover all the answers you need.